One would expect that when you build a wooden strip-planked kayak, it is made of wood. Well, yes—that is only partially correct. The ¼-inch thin strips of wood form the core of the kayak. They are like the eggshell of a chicken egg. Unfortunately, in its natural state, the type of wood we use in building these kayaks is soft and quite permeable. They will float in their natural state, but you have to coat them with a material that keeps the water out—not only of the kayak itself but the wood it is made from.

The early Inuit kayaks were made from whale bones and sealskin, which is naturally waterproof. As the whales and seals left, kayaks turned to wood. Initially they were covered in tar and pitch, or even special oils. Then along came petrochemicals, and we get polyester and vinylester resins, and now the more sophisticated epoxy resins. Epoxy resin is a chemical process rather than an evaporative process, so mix it correctly and it will harden. Heat only makes it more viscous.

Epoxy station

Now, having said that, resins have very little surface strength and bend easily. To address this in constructing a kayak, one adds a closely woven cloth (sometimes chopped mat) to the surface of the wood. This is then saturated with the epoxy resin and you get a very strong structure. Add a more sophisticated material like carbon fibre cloth and it gets better—but wait, there's more. Add kevlar woven into the carbon fabric and one, after adding resin, gets a very strong structure. You can jump on it and the ¼-inch wooden strips will not bend or break, so if you jump into the cockpit it will only flex.

Carbon fibre Kevlar cloth

Carbon fibre kevlar cloth is almost $100 a square metre, so for my kayak I have to use it very sparingly—in fact, only in the cockpit area. The professionals use vacuum bags to draw the resin onto and through the cloth and force the cloth directly onto the wood substrate. Well, again those bags are expensive and the vacuum pump well outside my budget. The result is applying the resin by brush and squeegee. It is a delicate process to get just enough resin to wet out the cloth and also to ensure no air bubbles are formed between the cloth and wood.

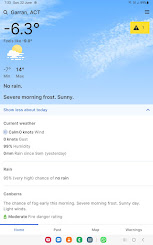

All of this is great in theory, and one can practise to perfect your technique, but the major variable in the whole exercise is the ambient temperature, which has to be above 11 degrees Celsius. Here in Canberra, ACT, Australia, we have—unlike those in Europe—been experiencing the longest cold stretch of night and day temperatures since reliable records have been kept. So each day I check the weather report and the temperature increase during the day to schedule the two epoxy days.

Weather forecast

The day arrived, but the weather forecast started badly: it is only -6.3°C but a high of 14°C. OK, that looked positive, so let's get started. I covered the side of the carport with a large blue sheet of plastic tarpaulin to try to keep the heat in and the wind out. Then set the diesel space heater to high as I watched the temperature in the work area rise above 11°C and on towards 20°C. The epoxy resin and hardener were placed over a large saucepan of slow boiling water to keep them warm. The cloth and kevlar had been sitting in the interior of the hull and deck all night, so there were no wrinkles.

Go—bring the wood, fibreglass cloth, carbon fibre kevlar and resin together in the right proportions. One has to work methodically and exactly, ensuring the mixture is always perfect. Never reuse a mixing cup, and try to disperse the resin before the chemical reaction in the cup starts to heat up. A fine balancing act.

Epoxy resin on the cloth

Both the hull and deck went according to plan, and I was able to complete the hull on day one and deck on day two before the temperature at five in the afternoon took a nosedive below zero. Both sets got tacky within two hours, so by lunchtime I was able to apply the first fill coat and by 5 PM the second fill coat. I trimmed the excess cloth soon after dinner, but the carbon fibre kevlar would not cut with either scissors or box cutter. The fill layers are smooth but not too thick. By morning most of the resin was hard, and by the expected 15 hours was quite hard.

Cloth completely wetted out

That was a big job completed. The major lesson learnt is don't start a fibreglass project in the middle of the Canberra winter unless you have a good heated room—why not my dining room?

The cockpit coaming and internals is the next big stage of the kayak project.